El arte que vive

A Xixon.

Hace unos días visité el Centro de Arte Nacional Museo Reina Sofía, y hay dos cosas que quiero destacar de aquella visita. La primera es una anécdota sobre El Guernica y la segunda, en parte consecuencia de la primera, es sobre El Profeta, la escultura de Gargallo. Cuadro y escultura se encuentra en salas contiguas, el Guernica está protegido por una cuerda que obliga al espectador a situarse lejos del cuadro, unos dos o tres metros. Ese espacio que se levanta entre obra y espectador es un vacío. Un abismo. En esta zona del museo además no se pueden hacer fotos, consecuencia de la sobreprotección a la que someten al cuadro de Picasso.

Hace unos días visité el Centro de Arte Nacional Museo Reina Sofía, y hay dos cosas que quiero destacar de aquella visita. La primera es una anécdota sobre El Guernica y la segunda, en parte consecuencia de la primera, es sobre El Profeta, la escultura de Gargallo. Cuadro y escultura se encuentra en salas contiguas, el Guernica está protegido por una cuerda que obliga al espectador a situarse lejos del cuadro, unos dos o tres metros. Ese espacio que se levanta entre obra y espectador es un vacío. Un abismo. En esta zona del museo además no se pueden hacer fotos, consecuencia de la sobreprotección a la que someten al cuadro de Picasso.

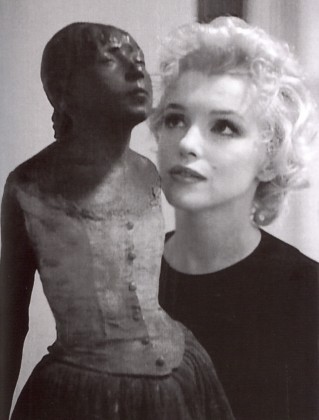

Me imagino el álbum de esa niña francesa, a la que le dijeron que las instantáneas estaban prohibidas, en su casa, colocando una imagen negra en el espacio del álbum que debería ocupar el Guernica. Mi cabreo fue en aumento cuando no me pude hacer un selfie al lado de El Profeta de Gargallo, copiando el gesto de Marilyn Monroe con la bailarina de Edgar Degas. Sin haber abandonado el museo le comenté a mi acompañante que todo esto era absurdo, que paseábamos por un cementerio donde las obras estaban embalsamadas donde los tiempos luchaban entre sí.

Me imagino el álbum de esa niña francesa, a la que le dijeron que las instantáneas estaban prohibidas, en su casa, colocando una imagen negra en el espacio del álbum que debería ocupar el Guernica. Mi cabreo fue en aumento cuando no me pude hacer un selfie al lado de El Profeta de Gargallo, copiando el gesto de Marilyn Monroe con la bailarina de Edgar Degas. Sin haber abandonado el museo le comenté a mi acompañante que todo esto era absurdo, que paseábamos por un cementerio donde las obras estaban embalsamadas donde los tiempos luchaban entre sí.

Un lugar donde relacionarse con la obra de arte era casi misión imposible. Un museo que no espera un espectador cómplice sino un espectador pasivo que únicamente mire. Un espacio del desencuentro.

Días después pensé en la experiencia que había supuesto para mí ver National Gallery (íd.,2014) de Frederick Wiseman. Pensé en el día que pasé cuando estuve en Londres visitándola y en las sensaciones que pude revivir al ver el documental. En definitiva, lo diferente que había sido la experiencia, lo vivo que se sentía un museo en comparación al otro y me pregunté los porqués. El documental realiza varias  preguntas a lo largo del metraje, ¿cómo se actualiza la importancia de la obra de arte en nuestro tiempo presente? Y ¿por qué no es suficiente con apelar a su valor de obra de arte? ¿Cómo se convierte la obra en algo vivo que nos habla? Y sobre todo, ¿por qué la obra pide algo más que la mirada pasiva del espectador?

preguntas a lo largo del metraje, ¿cómo se actualiza la importancia de la obra de arte en nuestro tiempo presente? Y ¿por qué no es suficiente con apelar a su valor de obra de arte? ¿Cómo se convierte la obra en algo vivo que nos habla? Y sobre todo, ¿por qué la obra pide algo más que la mirada pasiva del espectador?

El trabajo que traza Wiseman a lo largo de las casi tres horas es concienzudo, nos invita a conocer el museo desplazándose no solo por las cuatro zonas en las que está dividida la National Gallery también por los distintos departamentos adjuntos: laboratorios de conservación y restauración, salas de educación, talleres de pintura, foros de encuentro… incluso somos testigos de reuniones de la junta directiva del museo. En la National Gallery trabajan para hacer del arte algo vivo, algo que insertar en nuestras vidas, eso significa además, darles nuestra(s) historia(s), además de nuestra mirada, llenarlas de nosotros mismos.

Es hacer a los diferentes cuadros de la colección hablar-ahora, sentirlos además de entenderlos.

Es hacer a los diferentes cuadros de la colección hablar-ahora, sentirlos además de entenderlos.

Lo que Frederick Wiseman nos cuenta en su documental es una concatenación de encuentros, el de la Historia del Arte con la historia más personal (ese pasado que no cesa de venir enredado con ese presente en continuo, ese fantasma obra-de-arte que se encarna mediante nosotros.), lo fantasmático encuentra la carne. Y es también, un encuentro entre disciplinas cine y arte, arte y danza…

Todo este arte, parece decir National Gallery, vuelve a la vida a través de vosotros que miráis. Ese museo virtual que pertenece solo al espectador, y que es su imaginario, ese espacio-rompecabezas, donde se inserta la obra de arte vista y que empieza a dialogar con todo lo demás… ese es el lugar al que la National Gallery, como institución, y Frederick Wiseman apelan continuamente con sus imágenes. Es justo ahí, donde cuadro, película y canción comienzan a (re)vivir y resucitan. Este redecir la obra, el hecho de  actualizarla para las nuevas audiencias, entre las que se encuentran niños, invidentes, o en definitiva cualquiera que quiera estar una hora o diez en el museo, es el propósito que prevalece entre todos los testimonios que tienen lugar a lo largo del documental.

actualizarla para las nuevas audiencias, entre las que se encuentran niños, invidentes, o en definitiva cualquiera que quiera estar una hora o diez en el museo, es el propósito que prevalece entre todos los testimonios que tienen lugar a lo largo del documental.

National Gallery habla en presente, en está-pasando, en el “estamos creándole a la obra tantos relatos como espectadores se acercan a mirar un cuadro”.

Parte fundamental del documental lo ocupan los guías del museo, en sus discursos cuando explican los cuadros hay siempre una mezcla entre la referencia histórica al contexto en el que surgió la obra y su autor, y también, un “traer a la obra al presente”, o si prefiere, estimular el encuentro entre el cuadro y él que lo observa, y todo lo sensorial y todos los mecanismos que esa aproximación despierta. El guía no se limita a llevarte por el museo, no reduce su trabajo a señalarte el detalle que hace de un cuadro en concreto algo imprescindible para la Hª del Arte, sino que te acompaña y quizá lo que es más importante, te enseña a  experimentarla. Algo que es prueba de este espíritu narratológico desde lo sensorial y el sujeto es la escena en la que a un grupo de invidentes les están enseñando a ver con las manos una obra de Camille Pisarro, para ello, les invitan a tocar unas reproducciones del mismo cuadro en relieve con los elementos importantes de la obra.

experimentarla. Algo que es prueba de este espíritu narratológico desde lo sensorial y el sujeto es la escena en la que a un grupo de invidentes les están enseñando a ver con las manos una obra de Camille Pisarro, para ello, les invitan a tocar unas reproducciones del mismo cuadro en relieve con los elementos importantes de la obra.

Toda esta reflexión del arte que se encuentra con la vida, y el espectador que se encuentra con el arte y lo experimenta, es sin duda el tema que recorre el documental de Wiseman y lo vertebra a través de los diferentes espacios a los que el director nos invita a asistir. En la sala de restauración por ejemplo vemos Frederick Rihel a caballo, 1663 de Rembrandt que después de más de trescientos años ha desvelado gracias a la tecnología que el cuadro escondía otro anterior.

Si los museos no dan la espalda a la tecnología que hace que el cuadro nos cuente nuevas historias, tampoco debe dar la espalda y despreciar las formas en las que hoy nos comunicamos.

Volviendo a mi introducción al texto me atrevo a decir que debería ser inadmisible para la dirección de un museo que cualquier tumblr diera más vida al Guernicaque el Guernica mismo.

Se preguntan en el documental “¿cuál es el tiempo de un cuadro?”, probablemente la respuesta sea el tiempo que la tecnología y las artes sean capaces de conservarlo pero lo importante es, ¿cuánto vive el cuadro en ti después de que lo has mirado, después de haber entrado en tu historia, después de que te ha golpeado… ¿cuánto vivirá los bañistas de Asnieres en mí?

Frederick Wiseman propone un viaje por lo bello, y un viaje que ayuda a entender lo bello. Es además una exaltación de lo vivo, donde explicar y sentir un cuadro es ante todo una narración donde se encuentran lo espiritual con lo emocional y también con lo anecdótico, donde pasado y presente convergen creando un vínculo donde el punto central es el que está mirando. Hacer que todas esas obras choquen con la vida se traduce también en el documental en ese momento cuando en los últimos minutos dos bailarines perfoman el arte bailando delante de unos cuadros de Tiziano. En ese instante se crea una perfecta simbiosis entre la cámara que registra, el cuadro pintado, el baile y la música. La obra entonces parece palpitar y el museo se llena de la vida.

creando un vínculo donde el punto central es el que está mirando. Hacer que todas esas obras choquen con la vida se traduce también en el documental en ese momento cuando en los últimos minutos dos bailarines perfoman el arte bailando delante de unos cuadros de Tiziano. En ese instante se crea una perfecta simbiosis entre la cámara que registra, el cuadro pintado, el baile y la música. La obra entonces parece palpitar y el museo se llena de la vida.

Déborah García Sánchez-Marín

English version —>

To Xixon

A few days ago I went to the Reina Sofía National Art Centre, and I want to highlight two things about that visit. The first one is an anecdote about Guernica and the second one, which is in part consequence of the first, deals with Gargallo’s sculpture The Prophet. The painting and the sculpture are in adjacent rooms, Guernica is protected by a rope that forces the viewer to stay far from the picture, about two or three meters. That space built between artwork and spectator is a vacuum. An abyss. Also, in this zone of the museum it is not allowed to take photographs, as a consequence of the overprotection to which Picasso’s painting is put through.

I can imagine the album of that French little girl, who was told that snapshots were prohibited, at home, putting a black image in the location destined to Guernica. I was even more pissed off when I couldn’t take a selfie beside Gargallo’s Prophet, copying Marilyn Monroe’s gesture with Degas’ Little Dancer. Before leaving the museum, I told my companion that it was nonsense, that we were walking around a cemetery where all works were embalmed, where times fought each other.

A place where one could relate to the work was almost impossible to find. It was a museum which didn’t want an accomplice spectator, but a passive viewer, who just watched. A place of non-meeting.

A few days later I thought of the experience that was for me the projection of Frederick Wiseman’s National Gallery (2014). I thought of the day I spent in London, visiting the museum, and the feelings I could revive watching the documentary. Ultimately, how different was the experience, how alive that museum felt in comparison to the other, and I wondered why. The documentary asks some questions during its footage: how does the relevance of the work of art update to our present time? And, why invoking its status as a work of art isn’t enough? How does the oeuvre become something alive, which talks to us? And, above all, why does the oeuvre asks for something more than the passive glance of the viewer?

The work displayed by Wiseman during the almost three hours of running time is thorough. He invites us to become acquainted with the museum by touring not just the four zones the National Gallery is divided into, but also the different adjacent departments: preservation and restoration labs, education rooms, painting studios, forums… we even witness the meetings of the museum’s management board. In the National Gallery, people work to transform art into a live thing, something we can introduce in our lives. That means also giving it our own story (stories), in addition to our glance, fill it with ourselves.

It means making the paintings talk, it means feeling them, instead of just understanding them.

What Frederick Wiseman depicts in his documentary is a series of meetings: the meeting between Art History and a more intimate story (a past which keeps getting entangled with a present continuous, that ghost work-of-art which becomes incarnate through us). The phantasmagoric meets the flesh. And it is also an encounter between film and art disciplines, art and dance…

All that art, seems to say National Gallery, comes back to life through you who look. That virtual museum that belongs only the watcher, and which is his or her imaginarium, that space-puzzle, where to insert the contemplated work of art and which starts to talk to everything else… that is the place the National Gallery -as an institution- and Frederick Wiseman invoke constantly through their images. It is exactly there, where painting and film, movie and song start to (re)live and resurrect. This process of retell the oeuvre, the deed of update it for new audiences, which include children, blind people or, in short, anyone who wants to spend an hour or ten in the museum, is the purpose that prevails among al the testimonies scattered around the footage.

National Gallery speaks in present, in it-is-happening-now, in “we are creating as much tales for the piece of art as viewers come to look at a painting”.

A decisive part of the documentary belongs to the museum guides. When they explain the paintings, in their speeches there is always a mixture between the historical reference to the context in which the painting was born, and also an intent of bringing the work to the present, or, if you may, encourage the meeting between the painting and the observer, and everything sensory, and all the mechanisms that approach arouses. The guides doesn’t merely take you through the museum, doesn’t narrow their work to point the detail which makes a particular painting something essential in Art History, but also accompany you and, maybe the most important thing of all, they teach you to experience it. Something that proves that narratological approach from the sensory and the subject es the scene in which a group of blind people is being taught to see with their hands a work by Camille Pisarro. In order to do that, they are encouraged to touch 3D embossed reproductions of the same painting, with its main elements.

All this reflection on art meeting life, and the viewer meeting art and experiencing it, is without a doubt the major theme that runs through Wiseman’s documentary and that vertebrates it through the different spaces the director invites us to visit. In the restoration room, for instance, we can see Rembrandt’s Frederick Rihel on Horseback (1663), which after more that three hundred years has revealed, thanks to technology, that it was concealing another previous painting.

If museums don’t turn their back on the technology that makes the painting tell us new tales, they shouldn’t turn their back on or despise the ways we communicate today.

Going back to the beginning of the text, I daresay it should be inadmissible for a directing board of a museum that any tumblr gave more life to Guernica that Guernica itself.

The documentary asks “¿what is a painting’s lifespan?”. The answer is, probably, the time technology and arts are able to preserve it. But what matters is, how long does the painting live inside you after you’ve looked at it, after having entered your own history, after it has struck you… how long will Bathers at Asnières live inside me?

Frederick Wiseman offers a trip through beauty, and a trip that helps to understand beauty. It is also an exaltation of living things, in which explaining and feeling a painting is, above all, a narration where spiritual and emotional, and also anechdote, meet. Where present and past converge creating a link in which the central point is the watcher. Making all those works clash with life is also reflected in the documentary in the scene where, in the film’s last minutes, two dancers perform art dancing in front of several Tizziano’s paintings. In that moment, a perfect symbiosis between the recording camera, the painted picture, dance and music arises. The oeuvre then seems to pulsate and the museum gets filled with life.

English Translation: Juanma Ruiz